|

San Vitale 2 |

|

| Should any contemporary politician, or even a monarch, present themselves as a new Christ, or insist that they be portrayed with a halo, a psychoanalyst somewhere would almost certainly come up with a complicated name for the condition they were suffering from and they would be quietly lead away. These days, religion and politics, in western cultures at any rate, are strictly compartmentalised. Not so in the sixth century. I'm going to look at three mosaics in the Apse. The first, in the vault, shows a young, beardless Christ sitting on a blue sphere, with an archangel on either side. On Christ's right is Saint Vitale, and Christ is handing him a crown. On his left is Bishop Ecclesius, carrying a model of the church he founded. In his left hand Christ is holding the scroll with seven seals. |

|

|

|

|

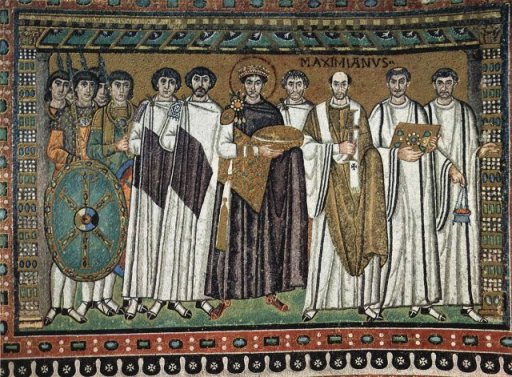

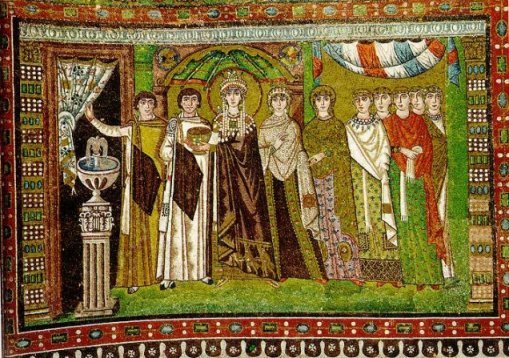

| If this is the

court of heaven, below it on either side are images of the court on

Earth. One shows Justinian, suitably haloed. Opposite it is the

Empress Theodora. The identity of

the other characters in the two panels has been hotly debated by scholars in those

papers that are always courteously respectful to those deadly academic rivals that disagree, but nevertheless endeavour to stick the knife in

right up to the hilt. One thing to note straight away - compared with those in the sanctuary, these figures are stiff and formal, but nevertheless are distinctive and seem to be portraits drawn from real life. |

|

|

|

|

| So what is going on here? On Justinian's right are two important looking men, one younger and one older. To the side of the them is a band of armed soldiers. On the other side of Justinian there is a figure looking over his shoulder, a bald bishop called Maximian, and two deacons. Justinian is holding a paten, and deacons are holding a gospel and a censer. Ecclesius up there in the vault initiated the building of the church - he died in 532 so it is quite right that he should be shown in Heaven. Maximius, Bishop and later Archbishop of Ravenna, died in 556, some nine years after the consecration of the church. It has been reasonably suggested that these panels must date after 540, the date when the Arian Ostragoths were driven out of Ravenna. The Ostragoths may have been tolerant of the orthodox Christians, but images showing their hated political rivals in triumph would not have gone down well. So is the mosaic of Justinian a work of political propaganda rather than religious devotion? Justinian and Theodora are leading their followers to the altar with gifts for Christ, and Maximian and his attendant deacons are prominent. this does suggest that the images are essentially devotional. But Maximian was very much a political appointee, sent to Ravenna from the east by Justinian. Could the images of Justinian and Theodora be more about their own importance than their humility? Suggestions for who the other characters depicted are is made in an engrossing paper by Irina Andreescu-Treadgold and Warren Treadgold, Procopius and the Imperial Panels of S. Vitale. * In their words, 'The panels may be compared to a modern photograph or videotape of an American President standing beside candidates of his party who face a difficult election campaign. The point is not so much to emphasise the great man's authority, which is taken for granted, but rather to show that his loyal but embattled subordinates enjoy his favour, and can count on his help and support. ' The paper proposes that the bearded man on Justinian's immediate right is Flavius Bellisarius, the general of the Byzantine Army that defeated the Ostragoths and took Ravenna. In the other panel, his wife, Antonina, stands to the left of Empress Theodora. Next to her in green is, it is claimed, Anatonina's daughter Joannina, who was engaged to be married to the young man next to Bellisarius, called Anastasius. Anastasius was a grandson of Theodora. |

|

|

|

|

| It seems that, in the later 540s Maximian, Bellisarius, and others in the inner circle that ruled Ravenna were in trouble. The Ostragoths were resurgent, and Maximian was deeply unpopular with the Citizens of Ravenna. They needed some support - but Justinian never came to Ravenna. So the next best thing was a demonstration, in mosaic, of the Emperor's implied divinity, and their firm links to him. It's a convincing story. If you can't get hold of the paper itself, Wikipedia has good articles on the main characters and their complicated lives. A complex story that underlines, I suppose, my comment on the last page; art such as this is rarely mere decoration. There is one last question. Why the marked difference in style between these mosaics and the ones in the sanctuary? It would seem that they were all created at roughly the same time. Could a different team of mosaicists have been involved? Possibly, but artists at the time were not expected to do their own thing. Here's an alternative idea. Maybe the rather old-fashioned, formal style was considered more appropriate for the depictions of, yes, Christ, saints and angels, but most of all for the Emperor and Empress. |

|

|

A

Reflection on apses. But what about the scenes of the Emperor on the side walls? Shouldn’t these be regarded as sacrilegious in such a sacred space? Again, I think, we need to consider historical context. As I’ve suggested earlier, modern notions of the divide between sacred and secular do not reflect beliefs of the sixth century. Emperors were appointed by God. Here is Eusebius’s description of the Emperor Constantine at the Council of Nicea: ‘At last he himself proceeded through the midst of the assembly, like some heavenly messenger of God, clothed in raiment which glittered as it were with rays of light, reflecting the glowing radiance of a purple robe, and adorned with the brilliant splendour of gold and precious stones.’ (The life of Constantine). (Eusebius is not being ironic – he was a great fan of Constantine.) a further thought occurs at this point. Apses weren’t a Christian invention. Roman basilicas, such as The Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine in the Forum, had an apse, and this was where the most important people sat. Particularly relevant is that this was the location of the seat of the judge in trials – the seat of judgment. So, at this time, the link between this space and judgment would have been perfectly familiar.

|

|

* Art Bulletin vol 79/4, Dec 1997. This paper and many others can be accessed at the excellent JSTOR site at www.jstor.org. |

|